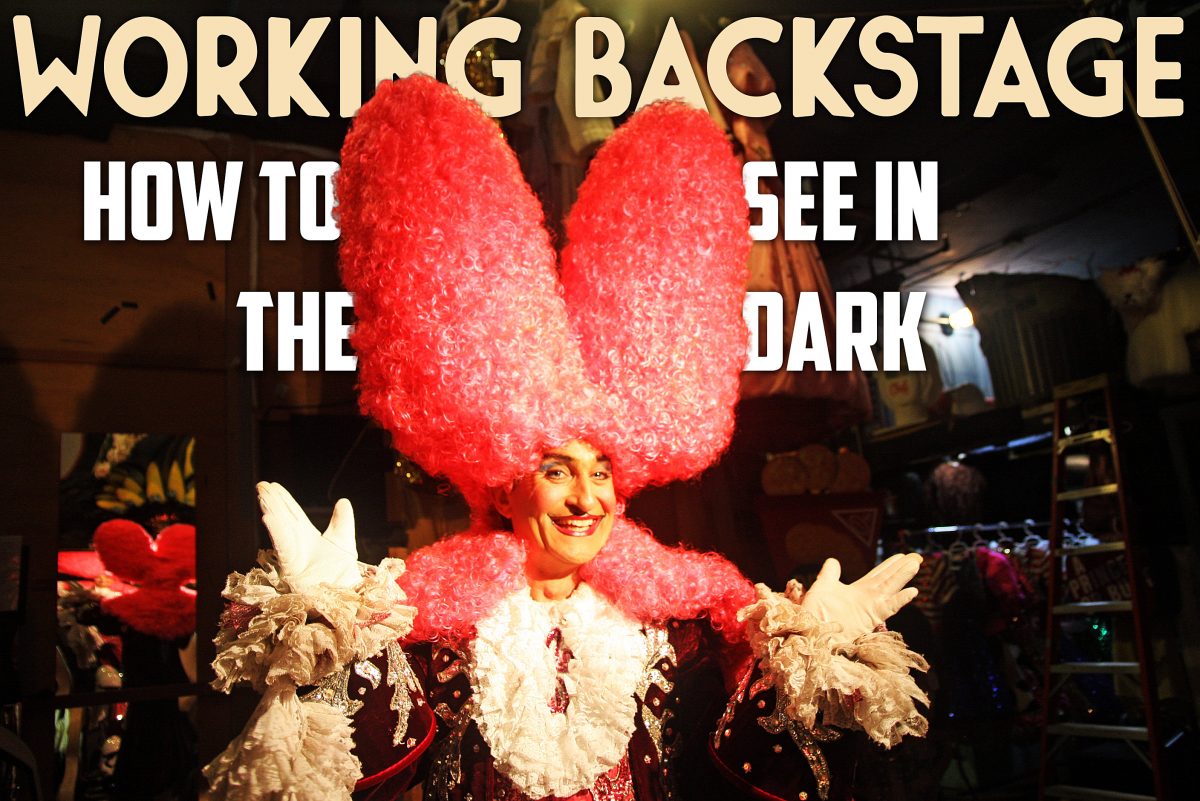

Sewing machines and supplies aren’t exactly the most portable things. Sometimes, when I’m not working fulltime on a show, I’ll get a one or two day job that requires me to schlep a machine and supplies to a work space. These are my least favorite kind of jobs – for no other reason than I have to transport my machine and a small kit of sewing supplies somewhere.

I live in New York City. I haven’t owned a car in over ten years.

What’s the big deal, you may ask, just throw it all in your car and go. Well, that’s the thing: I live in New York City. I haven’t owned a car in over ten years. The last time I drove was about two years ago. And I’m not a huge fan of Uber or even good old-fashioned yellow cabs. Cars are just not the most efficient way to get around the city. So, I’m usually dragging a sewing machine up and down the subway stairs to get to where I need to go.

On the go

I know I’ve recommended these machines before, but Brother makes some incredibly good and lightweight machines. I have two SC9500s. They are so lightweight that I carry them in a tote bag on my shoulder. I then use a backpack to carry my supplies: scissors, threads, rulers, chalk, a small collection of notions.

Other Brother machines that are very light weight are the CS5055 and the ES2000.

I also bike a lot, which is always the most efficient way to get around the city, and have been known to strap a machine (in a box) to the rear rack on my bicycle.

When going to a job that is only one or two days, sometimes it’s hard to figure out what to bring, especially if you’re trying to not lug your entire shop down the length of Manhattan and across the bridge to Brooklyn.

Here’s a list of what I usually bring to a short one-day job:

- 1 pair of tailor’s points or small scissors

- 1 pair of medium sized shears

- 1 pair of pinking shears (because I’m certainly not bringing a serger along to finish seams.)

- 1 gallon sized Ziploc of thread. Must have colors include black, grey, white, tan, a greeny-brown, nude, and a yellow-orange for topstitching on jeans.

- 12” see through 2” wide ruler

- 1 soft tape measure

- Tailor’s chalk, red marking pencil, pencil, black disappearing ink pen

- Seam ripper

- Metal hem gauge ruler

- Small container of straight pins

- Extra bobbins for machine

- Small collection of hand and machine needles (I always bring some leather needles and double needles, just in case.)

- 1 gallon sized Ziploc of bias tape (black and white), elastics, twill tape, and hem tape.

- Small containers of snaps and hook & eyes.

- Muslin pressing cloth

- Small collection of nude spandex and netting scraps and interfacings

Lighting is key

Sometimes it’s nice to bring along a small light of some kind. I often find myself sewing in inadequately lighted spaces. I tend not to bring a lamp because, well, the subway. I always make sure the light in the machine is working. And the flashlight on an iphone can be extremely helpful in especially dark circumstances.

Gear up

I’m not very high tech with my carrying cases but there are lots of really lovely ones out there if you’re not into backpacks and tote bags.

https://www.sewingmachinesplus.com/sewing-accessories-cases.php

The key is to keep everything super organized. And don’t worry about not having all the thread. Unless you’re topstitching, most things can be sewn with black, white, or tan. I know some tailors that only use those colors of thread. It really is ok if your thread doesn’t match exactly. And sometimes you just have to use what you have, especially if you are a traveling tailor.